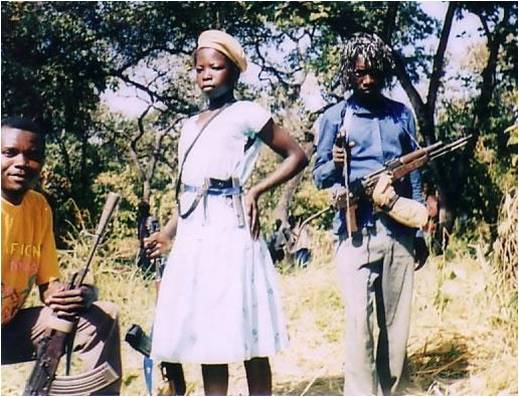

The iconic image of the African civil war is a savage young man armed with an AK-47. Young women, when they’re seen at all, are depicted as victims: mourning dead male family members, fleeing and searching for food, struggling to care for a child, or sexually abused.

This relegation to the status of vulnerable victims drives policy-making at the global level, donor funding in country, and program design on the ground. Too bad it’s only half the story.

Two years ago I ran a survey of women in northern Uganda with three colleagues–Jeannie Annan, Dyan Mazurana, and Khris Carlson. We interviewed hundreds of women formerly abducted, forced to fight, and sometimes forced to marry and bear children to rebel commanders. Most results came out quickly in a policy report and a brief to peace negotiators. After too long a delay, we’ve finally pulled together a shorter, more scholarly paper.

The newspapers make the Lord’s Resistance Army out to be a crazed charismatic group. But Kony’s gang is no irrational outlier. One argument we make is that the LRA has much more in common with disciplined, ideologically-committed rebel groups than they get credit for.

The LRA’s strategy–abduction and forced marriage, prohibitions on sex out of wedlock, and a complete ban on civilian rape–proved to be effective tools for building cohesion and maintaining control in the group. Too poor to pay its recruits, Kony built bonds of social control partly through sex. All too well, sadly.

This is not so rare as you’d think. My colleague Libby Wood has been writing lots about the strategic use of sexual violence in war. And once we understand the reasons for rape and forced marriage, we’re in a better position to combat it.

Besides tackling what role women played and why, we also ask: to what effect? The default, and understandable, view is that these women come home to unwelcoming families and a life of psychological distress.

Indeed, some do. What’s remarkable, though: the vast majority display resilience, not debilitating trauma, and most are accepted (even welcomed) by their families in short time. This finding implies a very different approach to aid–one that is much more targeted to the minority of most distressed women.

What’s equally amazing: unlike boy soldiers, abducted women and girls do not have lower education or income than their non-abducted peers. It’s hard to pinpoint why, but the most plausible explanation is also the most tragic: for females, life outside the rebel group held about as little opportunity as life inside. This is a sad statement on the school and job opportunities for women in northern Uganda.

The policy bottom line: more education and job opportunities for all women–not just former abductees–ought to be the priority after war. And we plan to prove it. See our experimental study on this site and in the Freakonomics blog.

The full paper is here. It’s a draft under review, so comments welcome.

One Response

Very interested in your study as I am currently preparing to do something to help the formerly abducted girls of Northern Uganda.