It was about the beginning of September, 1664, that I, among the rest of my neighbours, heard in ordinary discourse that the plague was returned again in Holland; for it had been very violent there, and particularly at Amsterdam and Rotterdam, in the year 1663, whither, they say, it was brought, some said from Italy, others from the Levant, among some goods which were brought home by their Turkey fleet; others said it was brought from Candia; others from Cyprus. It mattered not from whence it came; but all agreed it was come into Holland again.

We had no such thing as printed newspapers in those days to spread rumours and reports of things, and to improve them by the invention of men, as I have lived to see practised since. But such things as these were gathered from the letters of merchants and others who corresponded abroad, and from them was handed about by word of mouth only; so that things did not spread instantly over the whole nation, as they do now.

But it seems that the Government had a true account of it, and several councils were held about ways to prevent its coming over; but all was kept very private. Hence it was that this rumour died off again, and people began to forget it as a thing we were very little concerned in, and that we hoped was not true; till the latter end of November or the beginning of December 1664 when two men, said to be Frenchmen, died of the plague in Long Acre

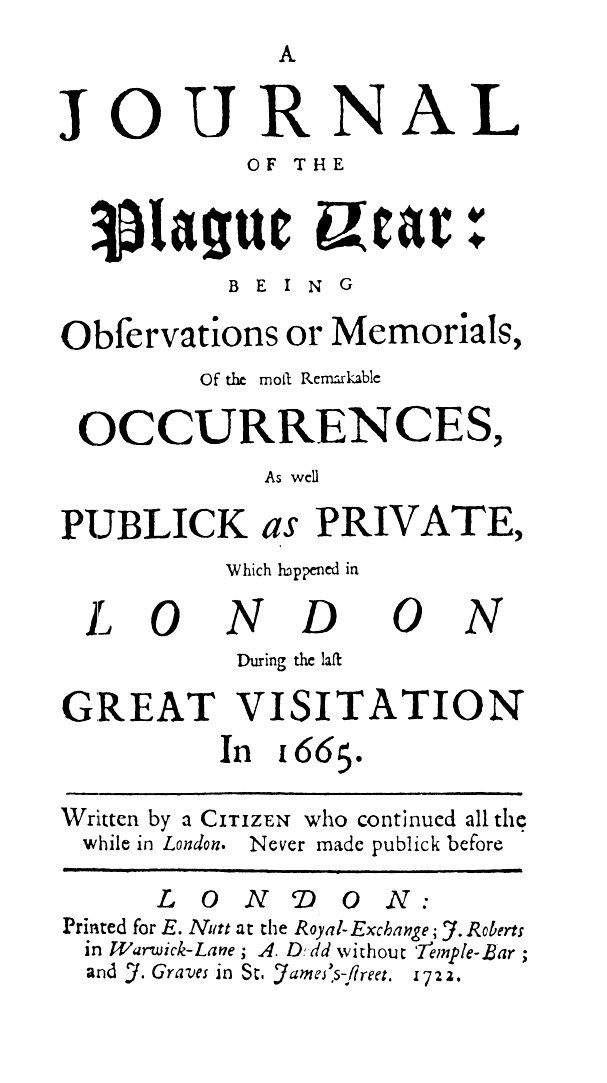

That’s from Daniel Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year [free online version], one Londoner’s eyewitness account of London’s last great bubonic outbreak, in 1665. It’s fiction. Defoe wrote it more than a half century after the great plague.

The disease crept through London’s outlying parishes from west to east. The earliest affected neighborhoods tried to conceal the cause of death, and falsified their numbers.

This turned the people’s eyes pretty much towards that end of the town, and the weekly bills showing an increase of burials in St Giles’s parish more than usual, it began to be suspected that the plague was among the people at that end of the town, and that many had died of it, though they had taken care to keep it as much from the knowledge of the public as possible

Instead of the New York Times‘ steady counts of infections by state, Defoe gives us tables of parish bills, showing the number of people buried in the neighborhood each week. From chapter to chapter, the figures grow higher and creep ever closer to his home, until he too is immersed in the misery and chaos.

The disease killed about an astonishing one quarter of London’s population in just 18 months. Defoe’s story, if nothing else, about human complacency and short-sightedness, even in the face of such mortality.

I often reflected upon the unprovided condition that the whole body of the people were in at the first coming of this calamity upon them, and how it was for want of timely entering into measures and managements, as well public as private, that all the confusions that followed were brought upon us, and that such a prodigious number of people sank in that disaster, which, if proper steps had been taken, might, Providence concurring, have been avoided, and which, if posterity think fit, they may take a caution and warning from. But I shall come to this part again.

There is even the 17th century version of Ivermectin and bleach!

they were as mad upon their running after quacks and mountebanks, and every practising old woman, for medicines and remedies; storing themselves with such multitudes of pills, potions, and preservatives, as they were called, that they not only spent their money but even poisoned themselves beforehand for fear of the poison of the infection; and prepared their bodies for the plague, instead of preserving them against it. On the other hand it is incredible and scarce to be imagined, how the posts of houses and corners of streets were plastered over with doctors’ bills and papers of ignorant fellows, quacking and tampering in physic, and inviting the people to come to them for remedies, which was generally set off with such flourishes as these, viz.: ‘Infallible preventive pills against the plague.’ ‘Neverfailing preservatives against the infection.’ ‘Sovereign cordials against the corruption of the air.’ ‘Exact regulations for the conduct of the body in case of an infection.’ ‘Anti-pestilential pills.’ ‘Incomparable drink against the plague, never found out before.’ ‘An universal remedy for the plague.’

It’s a long and unusually detailed book, with little plot or narrative drive, and yet still it’s fascinating and pulls the covid-afflicted reader along. It’s comforting in that it makes some sense of the reactions to our own own pandemic—the extremities in both ways—and depressing because it dispels my prior belief that, had this been a truly deadly disease, the world would have responded differently.