New York Times published an article last week, titled “The Future of Not Working.” In it, Annie Lowrie discusses the universal basic income experiments in Kenya by GiveDirectly: no surprise there: you can look forward to more pieces in other popular outlets very soon, as soon as they return from the same villages visited by the Times. One paragraph of the article drew my attention in particular: “One estimate, generated by Laurence Chandy and Brina Seidel of the Brookings Institution, recently calculated that the global poverty gap — meaning how much it would take to get everyone above the poverty line — was just $66 billion. That is roughly what Americans spend on lottery tickets every year, and it is about half of what the world spends on foreign aid.”

Well, I don’t know about you, but that paragraph makes me think that if we just were able to divert 50% of the current foreign aid budget towards cash transfers, we would eliminate extreme poverty. But, is that really true? The answer is: “not even close.”

That is World Bank economist and blogger Berk Ozler. His reasons are here. The short answer is “it is very hard to know who the poor are, find them, and know how much to give them in the form of jobs that pay cash enough to cover their families necessities”.

I would have added a couple more points. One is that we don’t really know what will happen when we scale up seemingly successful anti-poverty programs.

Also, I doubt there is long term political support in rich countries for a UBI for the poor, even if it were cheaper and more effective than our current aid programs. Mexico is already trying to figure out ways to get out from under the financial burden of its famous conditional cash transfers program. It’s such a big behemoth of a program that cash transfers draw more attention than the accumulation of many smaller but worse programs. They’re also unpopular among some. UK newspapers are already waging wars against Britain’s excellent cash transfer programs.

A successful UBI program for the poor has to find some political insulation, and have some paths for people to graduate out of it by getting wealthier.

My last comment: has no one reminded the “end of work” people that we’ve heard this claim every 20 years since the sewing machine and combine were invented? It’s possible that robots and AI mean it will be different this time. But I do not see the early warning signs. If structural unemployment will eventually be 60%, then at some point it will need to be 20%, and I don’t think we are even close. Wake me up when we see that happening.

17 Responses

But I do not see the early warning signs. If structural unemployment will eventually be 60%, then at some point it will need to be 20%, and I don’t think we are even close. Wake me up when we see that happening.

But I do not see the early warning signs. If structural unemployment will eventually be 60%, then at some point it will need to be 20%, and I don’t think we are even close. Wake me up when we see that happening.

golu dolls

golu dolls

This is no brainer. UBI is not for poor. It is fully exclusive. Even Bill Gates would get basic income. The idea of UBI is based on fact that for the first time in history productivity is so high that there is enough produced for all to have UBI covering for decent basic needs and plenty left for rich to compete. And once AI comes into game heavily even more so. UBI is not about money either it is about unconditional wealth distribution where all get same. Population control comes to game because each time we increase productivity by invention we increase in numbers. In 1966 there was 3.5 billion people on planet. We have double now. Quality needs to start ruling and quantity needs to step aside.

I enjoyed over read your blog post. Your blog have nice information,

I got good ideas from this amazing blog.

Thanks for sharing

@anon – ” wasteful and visibly-pointless make work.” Make-work for money is better than no-work for money.

In addition, the gov’t can learn in Public-Private-Partnership ways how to increase the value of the work by sending the workers as temps to where those willing to pay some, tho not all, costs are willing to pay something. Care for the elderly & very young, for instance.

Also “getting paid to learn a trade” — some can choose an apprenticeship and get the gov’t to pay them a bit to learn how to be a plumber.

Only work allows a worker to get the self-respect they need.

Have you read James Ferguson’s Give A Man A Fish? I find it compelling. Certainly unemployment among some groups within adult populations far exceeds 20%. Does it depend what we mean by employment? Ferguson is arguing for acknowledgement of the distributive economy. Where he works in Africa (mostly South Africa, & also the wider region), a lot of time and effort (i.e. work) goes into distribution, not production. He sees the expansion of various social welfare payments, even in countries as poor as Lesotho, as potentially (i.e. lots of caveats) transformative. A very large number of people in South Africa get a welfare transfer; the only group left is young men. The argument is not that cash transfers magically end poverty, but that they get at a neglected (and important) area of economic life.

The idea of a universal basic income is not bad, but difficult to execute. Destitute usually do not have identity cards, and it would be necessary to know their birth, deaths and income. But there is already a plan for recording the population. And the missing $ 66 billion is only 0.13% of the GDP of all rich countries combined. If the poor are so many what undernourished people, as seems likely, the person gets an average of 24 cents a day. This will increase the budget of the average person about 15% if the limit of extreme poverty is $ 1.90 a day.

We will therefore support the idea. You also can. http://f-f-a.info/join-us/

WC Varones:

> There are two general versions of UBI. One is a fantasy and the other is a misnomer.

I think you can have a check that pulls you much of the way up towards the poverty line, and also leads to reasonable (though by no means “low”, in absolute terms!) marginal tax rates at lower incomes. One should note that even a 50% or 60% marginal tax has very different effects from an 80% marginal tax, and a 100% marginal tax (which is what the “guaranteed income” proposal generally implies) is even more different from either. (Of course this is practically irrelevant to pure aid initiatives like the one the NYTimes article is talking about!)

Tom G, “Universal Basic Jobs” managed by the government amount to wasteful and visibly-pointless make work. The best way to encourage employment of low-income folks is by getting rid of burdensome taxes and regulations on low-skill jobs. As well as promoting education so that low-skilled folks can acquire some needed human capital.

What poor folk need are jobs, or better jobs.

Universal Basic Jobs would be the gov’t guaranteeing a job, or a job offer — with show up for work, do work, get money.

Then let the gov’t figure out what work to do to create value. It may well be that low-skill menial work in the US would create less value, say cleaning up an already somewhat clean part, than the gov’t cost to fund the job plus the supervisor.

Still, even these negative value jobs are better than no-strings basic income. In Kenya or Rwanda or other poor African countries, most poor are eager and willing to do higher value work, but need some entrepreneurial support to create a business, or to start working for a neighbor in the business created.

This won’t change even if robots do more work — tho it would be great if robots especially did more gov’t work, so the current gov’t employees could, instead, become business owners.

Shorter blog post: this time is not different, or, if man was meant to fly, he’d have wings! OK then everybody has an opinion.

Three rich countries already have universal basic incomes: Canada, Denmark, and New Zealand. So does Russia.

These countries have flat-rate pensions that are paid to all citizens and residents over the qualifying age.

You may wish to look at those populations to see what is happening.

There are many questions around UBI but I am leaning more and more towards becoming an advocate of the need for it. I think it is a consequence of the global economy’s need for constant annual growth. That need turns more and more production jobs over to intelligent machines (and it doesn’t help that their labor is not directly taxed since they are not paid a salary!). These machines boost output. And this is a really big change compared to previous industrial (r)evolutions!

And yes, building infrastructure for economical development in poor countries is a way of helping. But I don’t think it will reach the real poor. I see it as just another way of concentrating wealth in less and less people.

What the poor need, especially the ones at the grassroots, is help in their world, locally. I believe that change from the base with small amounts is achieving much more for these people then help from the top through for example financing a country’s infrastructure with billions. The help from the top rarely really arrives at the grassroots.

As for the Kenyan project discussed these days, I see it as a test run with a big potential for trouble. It is, as I understand it, divided in four segments: cash for 12 years, cash for two years, a lump sum and other villages without any help. This looks like a large field study to collect data on the relative impact of this kind of help. And all this happens in the same geographical area. I don’t think this is very respectful for the 4th group used as control and wonder if the potential psychological unrest it might provoke has been given any consideration.

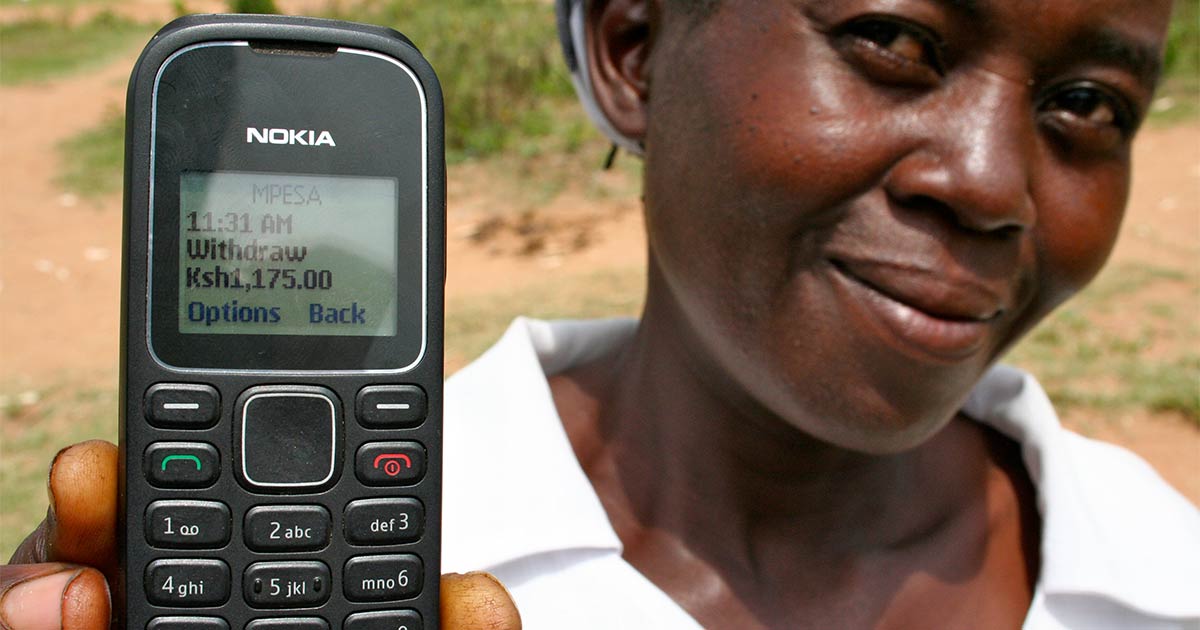

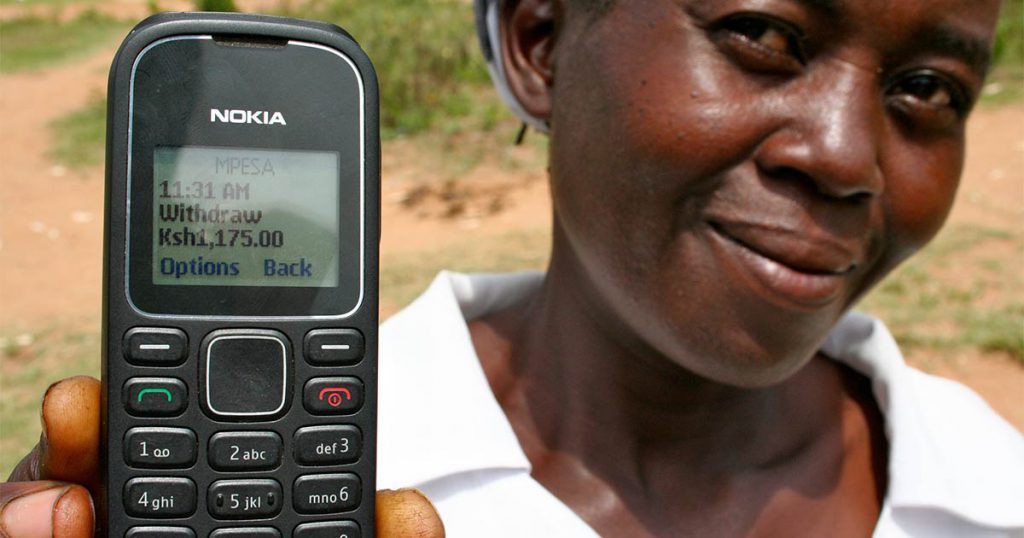

I believe however strongly in the ongoing help with small amounts at the grassroots, especially if you also provide experienced locals who are available for guidance. I think it is important to leave the locals in charge of their life and undertakings. Also, I have seen that a one-time big lump sum very seldom achieved a lasting improvement in a really poor population. But help with regular small amounts via an unexpensive system like M-PESA directly to the receiver can make a difference.

As for the effect of direct help (or UBI of any kind): the real poor in rural areas simply need it to get started towards our global economy. I think we should not and cannot compare a poor rural area in for example Africa with poor people in countries with highly developed infrastructure and a high GNP. I see the help with small direct payments in Africa as a good start towards developing local businesses. It gives people a purpose. And I think we can certainly say that the major part of humans need a purpose in life and that they are not afraid to work hard to fulfill that purpose. In Africa, the need at the grassroots is probably mainly to be able to eat, drink clean water and find shelter. Improved infrastructures in these poor rural areas would probably just allow us for example to even further exploit low cost sources of fodder for the animals in our meat factories which most often drastically increases the food cost for locals.

So, yes, I think UBI is a good thing, but may be we should think of it as a micro-investment with huge potential in poor rural areas and a real necessity in high GNP countries with increasing automation. We should not accept that people have to sleep in subway stations or under motorway bridges, but respect every human being, not only the material wealthy. A well structured UBI would most likely make a real difference.

“I don’t think we are even close”, really? Unemployment rate is the most recognized economic statistic but it is misleading. People that have given up looking for job opportunities (and have thus left the labor force) are no longer categorized as unemployed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ definition of unemployment. The employment rate is a much better indicator. By this broader measure, only 68% of the American population has worked in gainful employment for at least one hour in the previous week, down from its peak at 74% in 2000 (source: OECD).

There are two general versions of UBI. One is a fantasy and the other is a misnomer.

The fantasy is a check cut to every adult or every household that’s enough to provide for basic needs (i.e something like put everyone above the poverty line). Do the numbers. The amount of money required is absurd relative to federal budget & revenues.

The misnomer is really a guaranteed income, not universal. It gets paid only to the poor, and creates a huge marginal tax cliff for the working poor, which is one of the problems a UBI was supposed to eliminate.

“it is very hard to know who the poor are, find them, and know how much to give them”.

But the whole point of UBI is that you don’t need to build a bureaucracy dedicated to finding who is genuinely poor.

I agree that the $66 billion global “poverty gap” is nonsense. In most cases countries aren’t poor because they lack money, they lack money because they are poor. What makes countries wealthy is its infrastructure and/or capital base. It is roads, sewers, houses, farms, factories, schools, hospitals, etc. that make countries rich. Without these, a small cash income will do little to raise the quality of life in poor countries relative to what it is in wealthy countries (and isn’t that what we really want to accomplish?).

This was brought home to me several years ago when I suffered a life threatening medical problem. By good fortune I happen to live a short drive away from of one of the world’s top medical centers, the Mayo Clinic. I quickly recognized how much better off a monetarily poor person in a rich country is relative to a monetarily rich person in a poor country.

If extra income helps facilitates the construction of needed resources in some way, then it might have value. But I suspect that was not necessarily the goal of the Kenya project. Because of this I suspect helping poor countries build roads, schools, clinics, power plants, etc. will do more to raise people’s standard of living than a modest disbursement of cash.

That said, I’ll admit that I also currently align myself with the “end of work” crowd. I believe that this time it is different and we are already seeing the early warning signs.

This is admittedly oversimplified, but in a nutshell “work” is essentially a combination of physical effort and intelligent direction. Until recently (circa 1970), most of our machines were only able to enhance physical effort. A human was always required in some way to provide intelligent direction and people needed to be compensated for that effort. As the total value of goods and services being produced rose, so did the relative value of the human providing the intelligent effort required to keep the machines running.

The development of the computer appears to have changed this relationship and begun to reduce the need for human intelligence. The development of AI will likely complete the process and may soon make human operators in almost every economic activity unnecessary.

But if this is the case, why aren’t we seeing rising unemployment? I think we need to be careful about looking for early warning signs of this process in the employment numbers. Indeed I expect rising unemployment will be a lagging rather than a leading indicator.

Instead I prefer to watch for changes in the real economic value of work relative to the total value of goods and services being produced. There is a big difference between having a “job” and having a job that generates economic value. Just because a country is fully employed, doesn’t mean that the work being done has significant value (at least relative to total economic output).

Here is one of the possible early warning signs. This is a chart that depicts the ratio of total employee compensation (wages and salaries) relative to total gross domestic income (essentially GDP) in the US.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/W270RE1A156NBEA

You will note that this ratio was relatively constant at about 50% up until about 1980 when it began slowly declining. It currently stands at about 43%. What this seems to indicate is that the economic value of work has declined presumably because of increasing amounts of automation. Anomaly? It might be. But given the stagnation in real incomes over the past 30 years I’m not sure it can be dismissed quite so easily.

Anyway, I’ve written a couple of short articles on the matter if you are interested. Make of them what you will.

Automation and Inequality

https://pradlon.com/2017/01/02/automation-and-inequality/?iframe=true&theme_preview=true

The Decline of Brick and Mortar Retailing

https://pradlon.com/2017/01/20/the-decline-of-brick-and-mortar-retailing/?iframe=true&theme_preview=true

The Daily Mail is anti aid in general and aid funded cash transfers. That’s different from domestically funded welfare. The Mail’s all for pensions and hesitates to attack the popular UK child benefit. So I think there’s a distinction between aid funded cash transfers and domestically financed social assistance. Starting small with categorically targeted universal pensions and child benefits and gradually expanding can be politically popular. It was in the UK and shows signs of being so in places like Uganda, Zambia and Nepal. Finding the right role for aid in that mix is where it gets tricky.