If anti-poverty programs can pay for themselves in two or three years rather than twenty, wouldn’t that make sense?

Today I have a post in the WashPo’s Monkey Cage on programs that give livestock or cash plus training and other services, such as supervision and advising. Some recent studies, including one of mine, say these are cost effective programs that pay for themselves many times over.

True. And this is a big deal. But my post shows it could take decades. Always read the small print:

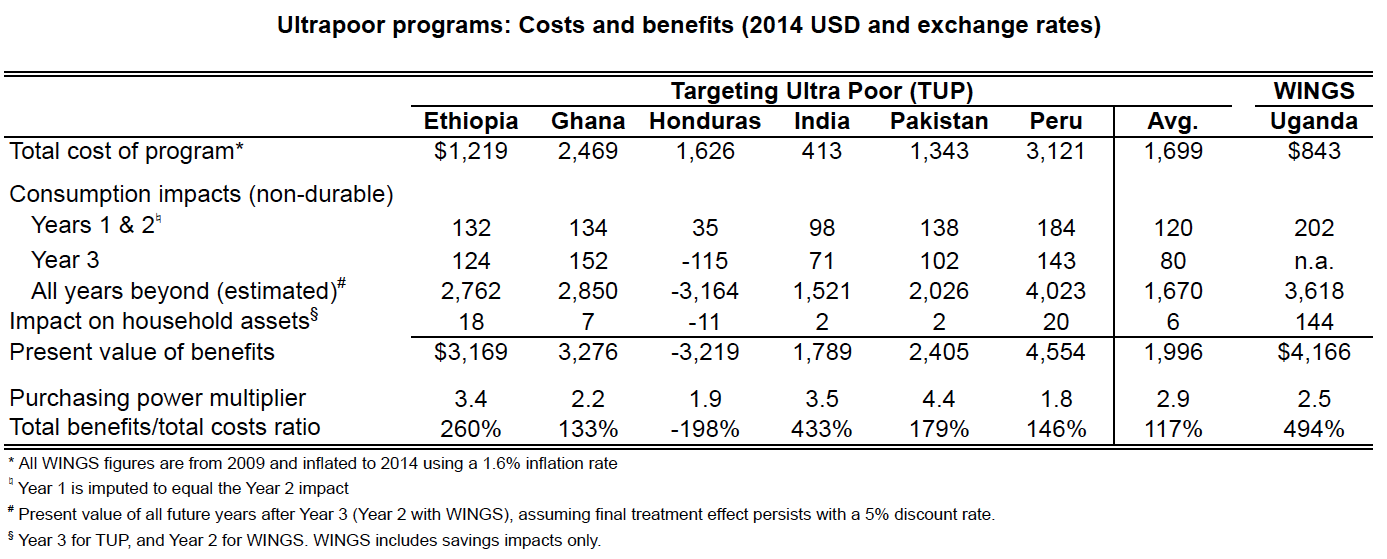

- Two to three years after the livestock or cash, all but one of these programs are raising the incomes of the poorest households by $71 to $202 a year. Since a dollar goes much further in poor countries, that’s actually $250 to $500 a year in purchasing power. that’s big.

- Unfortunately several of the programs cost one, two or even three thousand dollars per person, mainly because of heavy supervision time and other staff expenses.

- This means that, even with the high payoffs every year, the average livestock-plus program will take 18 years or more to break even. That’s not a number I have seen in the news coverage or calls for scaling up these programs.

- But the lower cost programs (including livestock-plus in India and cash-plus in Uganda) are paying off in three to five years. And their impacts are still high.

- Half the expenses are for supervision. What if we dropped this paternalism? If benefits fall by less than half, then the program breaks even much sooner.

- We tried this in Uganda. Compared to cash and training with expensive supervision, cash and training alone had almost identical effects on consumption after a year. Some businesses were more likely to stay open, and profits were a tiny bit higher. But it’s hard to believe supervision passes a cost-benefit test.

The message is clear: charities need to shift the burden of proof to high cost components such as supervision and training. We need to be laser focused on how many years for a program to break even. If three years is possible, why accept 20?

Read the full post. If you’re interested in my numbers, here’s the table I calculated from the Science paper and my own work. If you want purchasing power parity figures use the multipliers (or just times things by three in your head.) Click to expand.

15 Responses

I agree with Chris’s skepticism for impact into perpetuity (and also the discount rates used). I also support his call for reviewing costs which requires a deeper understanding of impact of component parts. However, I worry that continuing this review/conversation on the macro level misses potentially important findings at the micro-level of differences in types of poverty and those living in poverty. Treating all those living in poverty as one mass group masks important nuances that are noted in recent research studies. For example, Table 5 (and related appendices) in the multi-country study published in recent Science magazine looks at the impact of these types of programs by initial poverty quantiles (unclear if these were initial consumption or initial asset base). Other studies, including Chris’s in Uganda, look at segments such as youth, women, existing entrepreneurs—these segments seem to respond differently to the component mix within programs. I believe that we have enough data within the industry to begin to test tailoring these programs while trying to scale up.

Additionally, between these studies and between countries, there were important differences in the levels of asset transfer and savings requirements which may be very important to the calculations of sustained impact–are there “threshold” levels required?

I would like to see more research/review on the following:

1. Targeting (and related end-goal)

2. Segments and responses

3. Threshold levels of asset transfer/savings

Since the benefits of the program are clearly laid out, I’d assume there was some sort of inspection process for determining the benefits afterwards. Was that work part of the program, or seperate to the study?

I think if you are paring back the supervision side of things, there’d still be a need for some sort of follow-up to make sure the benefits are reaching the intended recipients. This presumably could be done with lower overhead through a sampling approach, but it would still involve some real expenses.

Does my logic follow there or am I missing something. I’ve previously looked at some of these issues from the perspective of local sourcing efforts for U.S. Department of Defense contracts in Afghanistan and Iraq. Obviously that’s a whole different set of problems, but it has prompted some past thinking on these issues, as total U.S. contract spending in Afghanistan was on the same order of magnitude as Afghan GDP.

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

I also wonder why those studies didn’t consider putting the per person funds in an annuity that pays out over their lifetime. This might have similar long term mental health and consumption benefits without the need for logistics and monitoring.

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5

RT @cblatts: The biggest barrier to ending poverty is… our paternalism? http://t.co/bVUz46VrI5